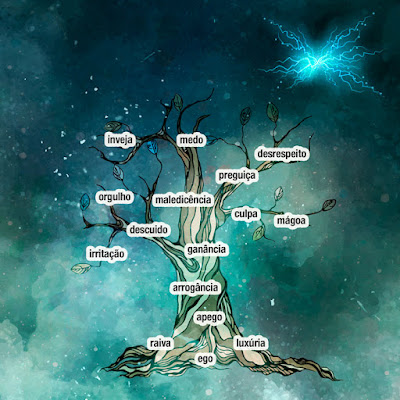

As virtudes e os vícios.

893. Qual a mais

meritória de todas as virtudes?

“Todas as

virtudes têm seu mérito, porque todas indicam progresso na senda do bem. Há

virtude sempre que há resistência voluntária ao arrastamento dos maus pendores.

A sublimidade da virtude, porém, está no sacrifício do interesse pessoal pelo

bem do próximo, sem pensamento oculto. A mais meritória é a que assenta na mais

desinteressada caridade.”

894. Há pessoas

que fazem o bem espontaneamente, sem que precisem vencer quaisquer sentimentos

que lhes sejam opostos. Terão tanto mérito quanto as que se veem na

contingência de lutar contra a natureza que lhes é própria e a vencem?

“Só não têm que

lutar aqueles em quem já há progresso realizado. Esses lutaram outrora e

triunfaram. Por isso é que os bons sentimentos nenhum esforço lhes custam e

suas ações lhes parecem simplíssimas. O bem se lhes tornou um hábito. Devidas

lhes são as honras que se costuma tributar a velhos guerreiros que conquistaram

seus altos postos.

“Como ainda

estais longe da perfeição, tais exemplos vos espantam pelo contraste com o que

tendes à vista, e tanto mais os admirais, quanto mais raros são. Ficai sabendo,

porém, que, nos mundos mais adiantados do que o vosso, constitui a regra o que

entre vós representa a exceção. Em todos os pontos desses mundos o sentimento

do bem é espontâneo, porque somente Espíritos bons os habitam. Lá, uma só

intenção maligna seria monstruosa exceção. Eis por que neles os homens são

ditosos. O mesmo se dará na Terra quando a humanidade se houver transformado,

quando compreender e praticar a caridade na sua verdadeira acepção.”

895. Postos de

lado os defeitos e os vícios acerca dos quais ninguém se pode equivocar, qual o

sinal mais característico da imperfeição?

“O interesse

pessoal. Frequentemente, as qualidades morais são como, num objeto de cobre, a

douradura que não resiste à pedra de toque. Pode um homem possuir qualidades

reais, que levem o mundo a considerá-lo homem de bem. Mas essas qualidades,

conquanto assinalem um progresso, nem sempre suportam certas provas, e às vezes

basta que se fira a corda do interesse pessoal para que o fundo fique a

descoberto. O verdadeiro desinteresse é coisa ainda tão rara na Terra que,

quando se patenteia, todos o admiram como se fora um fenômeno.

“O apego às

coisas materiais constitui sinal notório de inferioridade, porque, quanto mais

se aferra aos bens deste mundo, tanto menos compreende o homem o seu destino.

Pelo desinteresse, ao contrário, demonstra que encara de um ponto mais elevado

o futuro.”

896. Há pessoas desinteressadas, mas sem discernimento, que prodigalizam seus haveres sem utilidade real, por lhes não saberem dar emprego criterioso. Têm algum merecimento essas pessoas?

“Têm o do

desinteresse, porém não o do bem que poderiam fazer. O desinteresse é uma

virtude, mas a prodigalidade irrefletida constitui sempre, pelo menos, falta de

juízo. A riqueza, assim como não é dada a uns para ser aferrolhada num cofre

forte, também não o é a outros para ser dispersada ao vento. Representa um

depósito de que uns e outros terão de prestar contas, porque terão de responder

por todo o bem que podiam fazer e não fizeram, por todas as lágrimas que podiam

ter estancado com o dinheiro que deram aos que dele não precisavam.”

897. Merecerá

reprovação aquele que faz o bem sem visar a qualquer recompensa na Terra, mas

esperando que lhe seja levado em conta na outra vida e que lá venha a ser

melhor a sua situação? E essa preocupação lhe prejudicará o progresso?

“O bem deve ser

feito caritativamente, isto é, com desinteresse.”

a) — Contudo,

todos alimentam o desejo muito natural de progredir, para forrar-se à penosa

condição desta vida. Os próprios Espíritos nos ensinam a praticar o bem com

esse objetivo. Será, então, um mal pensarmos que, praticando o bem, podemos

esperar coisa melhor do que temos na Terra?

“Não,

certamente; mas aquele que faz o bem sem ideia preconcebida, pelo só prazer de

ser agradável a Deus e ao seu próximo que sofre, já se acha num certo grau de

progresso, que lhe permitirá alcançar a felicidade muito mais depressa do que

seu irmão que, mais positivo, faz o bem por cálculo e não impelido pelo ardor

natural do seu coração.” (894.)

b) — Não haverá

aqui uma distinção a estabelecer-se entre o bem que podemos fazer ao nosso

próximo e o cuidado que pomos em corrigir-nos dos nossos defeitos? Concebemos

que seja pouco meritório fazermos o bem com a ideia de que nos seja levado em

conta na outra vida; mas será igualmente indício de inferioridade

emendarmo-nos, vencermos as nossas paixões, corrigirmos o nosso caráter, com o

propósito de nos aproximarmos dos Espíritos bons e de nos elevarmos?

“Não, não.

Quando dizemos fazer o bem queremos significar ser caridoso. Procede como

egoísta todo aquele que calcula o que lhe possa cada uma de suas boas ações

render na vida futura, tanto quanto na vida terrena. Nenhum egoísmo, porém, há

em querer o homem melhorar-se, para se aproximar de Deus, pois que é o fim para

o qual devem todos tender.”

898. Sendo a

vida corpórea apenas uma estada temporária neste mundo e devendo o futuro

constituir objeto da nossa principal preocupação, será útil nos esforcemos por

adquirir conhecimentos científicos que só digam respeito às coisas e às

necessidades materiais?

“Sem dúvida.

Primeiramente, isso vos põe em condições de auxiliar os vossos irmãos; depois,

o vosso Espírito subirá mais depressa, se já houver progredido em inteligência.

Nos intervalos das encarnações, aprendereis numa hora o que na Terra vos

exigiria anos de aprendizado. Nenhum conhecimento é inútil; todos mais ou menos

contribuem para o progresso, porque o Espírito, para ser perfeito, tem que

saber tudo, e porque, cumprindo que o progresso se efetue em todos os sentidos,

todas as ideias adquiridas ajudam o desenvolvimento do Espírito.”

899. Qual o mais

culpado de dois homens ricos que empregam exclusivamente em gozos pessoais suas

riquezas, tendo um nascido na opulência e desconhecido sempre a necessidade,

devendo o outro ao seu trabalho os bens que possui?

“Aquele que

conheceu os sofrimentos, porque sabe o que é sofrer. A dor, a que nenhum alívio

procura dar, ele a conhece; porém, como frequentemente sucede, já dela se não

lembra.”

900. Aquele que

incessantemente acumula haveres, sem fazer o bem a quem quer que seja, achará

desculpa válida na ideia de acumular com o fito de maior soma legar aos seus

herdeiros?

“É um pacto com

a consciência má.”

901. Figuremos

dois avarentos, um dos quais nega a si mesmo o necessário e morre de miséria

sobre o seu tesouro, ao passo que o segundo só o é para os outros, mostrando-se

pródigo para consigo mesmo; enquanto recua ante o mais ligeiro sacrifício para

prestar um serviço ou fazer qualquer coisa útil, nunca julga demasiado o que

despenda para satisfazer aos seus gostos ou às suas paixões. Peças-lhe um

obséquio e estará sempre em dificuldade para fazê-lo; imagine, porém, realizar

uma fantasia e terá sempre o bastante para isso. Qual o mais culpado e qual o

que se achará em pior situação no mundo dos Espíritos?

“O que goza,

porque é mais egoísta do que avarento. O outro já recebeu parte do seu

castigo.”

902. Será

reprovável que cobicemos a riqueza, quando nos anime o desejo de fazer o bem?

“Tal sentimento

é, não há dúvida, louvável, quando puro. Mas será sempre bastante

desinteressado esse desejo? Não ocultará nenhum intuito de ordem pessoal? Não

será de fazer o bem a si mesmo em primeiro lugar que cogita, muitas vezes,

aquele em quem tal desejo se manifesta?”

903. Incorre em

culpa o homem por estudar os defeitos alheios?

“Incorrerá em

grande culpa, se o fizer para os criticar e divulgar, porque será faltar com a

caridade. Se o fizer para sua instrução pessoal e para evitá-los em si próprio,

tal estudo poderá algumas vezes ser-lhe útil. Importa, porém, não esquecer que

a indulgência para com os defeitos de outrem é uma das virtudes contidas na

caridade. Antes de censurardes as imperfeições dos outros, vede se de vós não

poderão dizer o mesmo. Tratai, pois, de possuir as qualidades opostas aos

defeitos que criticais no vosso semelhante. Esse o meio de vos tornardes

superiores a ele. Se lhe censurais o ser avaro, sede generosos; se o ser

orgulhoso, sede humildes e modestos; se o ser áspero, sede brandos; se o

proceder com pequenez, sede grandes em todas as vossas ações. Numa palavra,

fazei por maneira que se não vos possam aplicar estas palavras de Jesus: Vê o

argueiro no olho do seu vizinho e não vê a trave no seu próprio.”

904. Incorrerá

em culpa aquele que sonda as chagas da sociedade e as expõe em público?

“Depende do sentimento

que o mova. Se o escritor apenas visa produzir escândalo, não faz mais do que

proporcionar a si mesmo um gozo pessoal, apresentando quadros que constituem

antes mau do que bom exemplo. O Espírito aprecia isso, mas pode vir a ser

punido por essa espécie de prazer que encontra em revelar o mal.”

a) — Como, em

tal caso, julgar da pureza das intenções e da sinceridade do escritor?

“Nem sempre há

nisso utilidade. Se ele escrever boas coisas, aproveitai-as. Se proceder mal, é

uma questão de consciência que lhe diz respeito, exclusivamente. Ademais, se o

escritor tem empenho em provar a sua sinceridade, apoie o que disser nos

exemplos que dê.”

905. Alguns

autores têm publicado belíssimas obras de grande moral, que auxiliam o

progresso da humanidade, das quais, porém, nenhum proveito tiraram para a

própria conduta. Ser-lhes-á levado em conta, como Espíritos, o bem a que suas

obras hajam dado lugar?

“A moral sem as

ações é o mesmo que a semente sem o trabalho. De que vos serve a semente, se

não a fazeis dar frutos que vos alimentem? Grave é a culpa desses homens,

porque dispunham de inteligência para compreender. Não praticando as máximas

que ofereciam aos outros, renunciaram a colher-lhes os frutos.”

906. Será

passível de censura o homem por ter consciência do bem que faz e por

confessá-lo a si mesmo?

“Pois que pode

ter consciência do mal que pratica, do bem igualmente deve tê-la, a fim de

saber se andou bem ou mal. Pesando todos os seus atos na balança da lei de Deus

e, sobretudo, na lei de justiça, amor e caridade, é que poderá dizer a si mesmo

se suas obras são boas ou más, que as poderá aprovar ou desaprovar. Não se lhe

pode, portanto, censurar que reconheça haver triunfado dos maus pendores e que

se sinta satisfeito, desde que de tal não se envaideça, porque então cairia

noutra falta.” (919.)

O Livro dos

Espíritos – Allan Kardec.

Virtues and

Vices

893. Which is

the most admirable of all the virtues?

“All virtues are admirable, as they all are signs of progress on the moral path. Every act of voluntary resistance to the seductive influence of temptations for wrongdoing is a sign of virtue, but the sublimity of virtue entails the sacrifice of self-interest for the good of others without having any ulterior motives. The most admirable of all virtues is that which is based on charity and is the most fair-minded.”

894. Some people

do good spontaneously, without having to overcome any conflicting feelings. Is

there as much merit in their action as in that of others who have to struggle

to overcome the imperfections of their own nature in order to do good?

“Those who no

longer struggle against selfishness have already accomplished a certain amount

of progress. They have struggled and succeeded, and they no longer have to put

forth any effort into behaving morally or justly. Doing good is perfectly

natural to them, because kindness has become a habit that they have acquired.

They should be honored as veterans are. They have earned their medals.”

“As you are

still far from perfection, their behavior is astonishing to you because their

action contrasts so strongly with that of the rest of humankind, and you admire

it given its rarity. However, the exception in your world is the rule in more

advanced worlds. Goodness is everywhere in those worlds because they are only

inhabited by good spirits, and even a single foul intention would be considered

an exceptional monstrosity. That is why these worlds are happy and it will be

the same on Earth when the human race has been transformed, and understands and

practices the law of charity in its true meaning.”

895. Besides the

obvious faults and vices, what is the most characteristic sign of imperfection?

“Self-interest.

Moral qualities are too often like gilding on copper that cannot withstand the

acid test. Some individuals may possess good qualities that help them to appear

to be virtuous, but those qualities, despite proving that they have made a

certain amount of progress, may not be capable of standing trial. The slightest

disturbance of their narcissism is enough to reveal their true nature. Absolute

disinterestedness is so rare on Earth, that when you do encounter it you may

very well view it as a phenomenon.”

“Attachment to

material things is a sign of inferiority, because the more you care for the

things of this world, the less you understand your destiny. Your

disinterestedness, on the contrary, proves that you have a more elevated view of

the future.”

896. Are there

people who are indiscriminately generous and who dole out their money without

doing any real good due to their lack of a reasonable plan? Is there any merit

in their action?

“They have the

merit of disinterestedness, but not that of the good they might do. While

disinterestedness is a virtue, thoughtless spending reveals a lack of judgment,

to say the least. Fortune is no more given to some individuals to be thrown

away than to others to be locked up in a safe. This is a deposit for which they

will have to render an account. They will have to answer for all the good they

might have done, but also that which they failed to do. As well as all the

tears they could have dried with the money they wasted on those who did not

truly need it.”

897. Is it wrong

if people do good in the hope that they will be rewarded in the next life, and

that their situation will be better there for having done it? Will such an act

have unfavorable consequences on their advancement?

“You should do

good for the sake of charity, meaning disinterestedly.”

a) It is

completely natural to want to advance to be free from this painful life. The

spirits tell us to do good to reach this end. Is it wrong to hope that, through

doing good, we may be better off than we are on Earth?

“Of course not.

But those who do good impulsively, simply for the sake of pleasing God and

providing relief to their suffering neighbors, have already reached a higher

degree of advancement and are closer to reaching ultimate happiness than their

brothers and sisters who, being more selfish, do good in hopes of receiving a

reward, instead of being compelled by the goodness of their own hearts.” (See

no. 894)

b) Should a

distinction be made between the good we do for our neighbors and the effort we

put forward to correct our own faults? We understand that there is little merit

in doing good with the idea that we will be rewarded in the next life. Is it

also a sign of inferiority to fix ourselves, conquer our passions, correct

whatever flaws we may have, in the hope of bringing ourselves closer to good

spirits and elevating ourselves?

“No, by doing

good we merely mean being charitable. Those who count, in every charitable deed

they do, how much they will be rewarded, in this life or the next, act

selfishly. However, there is no selfishness in improving one’s self in the hope

of getting closer to God, which should be everyone’s goal.”

898. Physical

life is only a temporary stopover and our future life is what we should care

about primarily. Is there any point in trying to acquire scientific knowledge

that only refers to the objects and wants of this world?

“Of course there

is. This knowledge enables you to benefit humankind. Also, if your spirit has

already progressed in intelligence, it will rise faster in the spirit life and

learn in an hour what it would take years to learn on Earth. No knowledge is

useless since it all contributes to your advancement in one form or another. A

perfect spirit must know everything and progress must be made in every

direction. All acquired ideas help forward development.”

899. Out of two

rich individuals who both use their wealth solely for their personal

satisfaction, one was born into affluence and has never known want, the other

earned his or her wealth by personal labor, which is more shameful?

“The one who

knows suffering and does nothing to relieve it. He or she knows unrelieved pain

Too often, this person no longer remembers the difficulties it has endured.”

900. Can those

who constantly accumulate wealth, without doing good for anyone, find an excuse

in the fact that they will leave a large fortune to their heirs?

“This is a compromise

with a bad conscience.”

901. Imagine a

scenario with two miserly individuals. One forgoes the necessities of life and

dies in want surrounded by treasures. The other is self-indulgent and cheap

with respect to others. This person winces at making the smallest sacrifice for

others or serving a noble cause while the cost of indulging personal passions

is inconsequential. This individual is always short on funds when kindness is

asked for others, but has plenty of money to satisfy any of his own whims.

Which of them is more disgraceful? Which one will be worse off in the spirit

world?

“The one who

recklessly spends money on personal pleasures, because he or she is more

selfish than miser. The other is already undergoing a part of the atonement.”

902. Is it wrong

to wish for wealth as a means of doing good?

“Such a desire

is admirable when it is pure, but is it always truly disinterested? Don’t

people first desire to do good for themselves?”

903. Is it wrong

to study other people’s faults?

“To do so merely

for the sake of criticizing or exposing them is wrong, because it demonstrates

a lack of charity. To do so for your own benefit to avoid replicating those

flaws may sometimes be useful but you must not forget that understanding the

faults of others is one of the elements of charity. Before criticizing others

for their flaws, you should look at yourself and see if others could criticize

you for the same faults. The only way to profit by such a critical examination

of other’s faults is by trying to acquire the opposite virtues. Are those you

criticize cheap? Be generous. Are they proud? Be humble and modest. Are they

callous? Be gentle. Are they cruel and petty? Be great in everything that you

do. Basically, act in such a way so that it may not be said of you, in Jesus’

words, that you ‘see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not see the beam

in your own.’”

904. Is it wrong

to probe the plagues of society and revealing them?

“That depends on the motive behind this action. If a writer’s only purpose is to create a scandal, he or she obtains personal satisfaction from presenting images or situations that are corruptive rather than instructive. The mind perceives the evils of society, but those who take pleasure in portraying evil for the sake of evil will be punished for doing so.”

a) In this case,

how can we judge the purity of intention and the sincerity of the authors?

“It is not

always necessary. If authors write good things, you profit by them. If they

write bad things, it is a question of conscience. However, if they want to

prove their sincerity, do they do it by the excellence of their own example?”

905. There are

great books that are full of moral teachings from which their authors have not

derived much moral profit despite helping the progress of humanity. Is the good

those authors do by their writings be counted to them as spirits?

“Professing the

principles of morality without subsequent action is like having a seed without

completing the sowing. What is the point of having the seed, if you do not make

it bear fruit to feed you? These authors are even guiltier, because they

possess the intelligence that enables them to understand. By not practicing the

virtues they recommend to others, they fail to enjoy the harvest they could

reap themselves.”

906. Is it wrong

for those who do good to be conscious of the goodness of their deed, and to

acknowledge that goodness to themselves?

“Since human

beings are aware of the bad they do, they must also be aware of the good they

do as well. It is only by this recognition of their conscience that they can

know whether they have done good or bad. By weighing all their actions

according to God’s law, especially the law of justice, love and charity, they

can decide whether they are good or bad, and can approve or disapprove of those

actions accordingly. Therefore, it is not wrong to recognize the fact that they

have triumphed over evil and rejoice in having done so, provided that this does

not turn into narcissism, because that would be as reprehensible as any of the

faults over which they have triumphed.” (See no. 919)

The Spirits’

Book – Allan Kardec.

.jpeg)

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário